Glaucoma Surgery in Aniridia Patients

| Primary authors |

|

|---|

Aniridia patients present unique surgical challenges. Aniridia is a panocular disease that is associated with higher incidence of glaucoma and cataract. It is also associated with foveal hypoplasia, stem cell deficiency, nystagmus, and subluxated lenses. Approximately 50% of aniridia patients will develop aniridic glaucoma.[1] Many patients who develop aniridic glaucoma eventually require glaucoma surgery. Initially, it has been shown that some patients with aniridic glaucoma can be controlled with topical medicines.[2] When medications fail or ocular surface disease precludes adding multiple glaucoma drops, there are many different techniques that have been described in the surgical treatment of aniridic glaucoma. In addition, prophylactic goniotomy in a select group of younger aniridia patients may also be effective in preventing the development of aniridic glaucoma.[1]

Goniotomy

Chen and Walton[1] have described goniotomy as a prophylactic procedure in young ariridia patients (mean age 37 months) with iris adhesions to the posterior trabecular meshwork for greater than 180 degrees. This technique, in a select group of younger patients with early angle changes, may be effective in preventing aniridic glaucoma.[1] In their retrospective study that examined 50 eyes in 33 patients with aniridia, 49 (89%) had an intraocular pressure (IOP) <22 mm Hg without medications at last follow up. This was with an average of 1.65 procedures and average of 200 degrees of gonio-surgery. No operative complications were noted, and no eye had a decrease

in visual acuity at last follow-up. This series suggests that the incidence of glaucoma development in aniridia patients may be significantly affected by goniosurgery. Goniotomy requires an adequate gonioscopic view of the angle, which can which can become more limited if worsening aniridic keratopathy develops over time. This procedure may be a good option in some younger aniridia patients, before more severe aniridic keratopathy develops, which can limit a clear view of the angle.

Trabeculotomy

Trabeculotomy has also been shown to be a reasonable option in aniridia patients. The advantage of trabeculotomy is that it does not require a clear gonioscopic view and can be done in patients with corneal opacities that may limit the ability to perform goniotomy surgery. In a series of aniridia patients undergoing initial surgery for glaucoma, Adachi et al[3] found that 10 (83%) out of 12 eyes in trabeculotomy patients were controlled with 9.5 years of follow-up, compared with 3 (18%) out of 17 eyes that underwent goniotomy, trabeculectomy, traceculectomy combined with trabeculotomy, and Molteno implant.

Glaucoma Drainage Implants

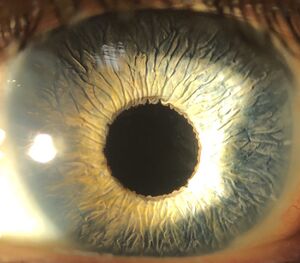

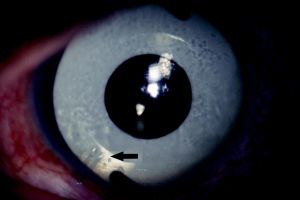

Glaucoma drainage implants are effective at controlling pressure in aniridic glaucoma. Molteno implants were effective at controlling pres-sure in 5 (83%) out of 6 eyes in a series by Wiggens and Tomey.[4] Similarly, Baerveldt glaucoma drainage implants have been shown to control IOP in aniridic glaucoma.[5] Success with Ahmed valves in aniridia patients with glaucoma has also been demonstrated, but some patients required needling and 5-fluorouracil.[6] Glaucoma drainage implants have been the treatment of choice in my practice for older patients with aniridia, and I have been very satisfied with the level of pressure control achieved with these techniques (Figure 1A and B). The surgeon has to be prepared to manage surface-related complications such as tube erosions, which may occur at a higher rate in patients with severe surface disease and stem cell deficiency (Figure 2).

Cyclodestructive Procedures

Traditionally, cyclodestructive procedures have been reserved for refractory glaucomas or glaucomas associated with a very poor visual potential. Cyclocryotherapy procedures have been described in aniridia with limited success. In a series by Wiggens and Tomey,[4] cyclocryotherapy was successful in only 25% of eyes, and complications such as phthisis bulbi and progressive cataract were observed. Wagle et al[7] reported a much higher rate of phithis using cyclocryotherapy in pediatric glaucoma patients with aniridia resistant to maximal medical and surgical interventions compared with pediatric patients with glaucoma not associated with aniridia. This study cautions the use of cyclodestructive procedures in aniridia patients with glaucoma. It remains to be seen whether other cyclodestructive procedures, such as endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation or transscleral cyclophotocoagulation, which have been used to treat secondary glaucomas in childhood,[8] have a place in the treatment of glaucoma associated with aniridia.

Trabeculectomy

Conflicting results have been reported in the literature with regard to the success of trabeculectomy for glaucoma in patients with aniridia. In a retrospective review of aniridic glaucoma patients under the age of 40 years following trabeculectomy (17 patients) and trabeculectomy with mitomycin C (MMC) (3 patients), the mean period of postoperative suc-cess (defined as IOP below 21 mm Hg with or without medicines) after the filtering surgery was 14.6 months (range: 2 to 54 months).[9] Other studies have shown minimal benefit of trabeculectomy in aniridia. Wiggens et al[4] found that trabeculectomy controlled the IOP in only 9% of cases in which it was performed.

Special Concerns With Aniridia Patients

Central Corneal Thickness

Central corneal thickness has been shown to be increased in aniridia patients, which is an important consideration when measuring IOP by Goldmann applanation tonometry in these patients.[10][11] Clinicians may be overestimating IOP when using Goldmann applanation tonometry techniques in aniridia patients with increased central corneal thickness.

Surface Disease

Stem cell deficiency and ocular surface disease are special concerns that occur in patients with aniridia. In some patients with aniridia, the surface failure can be successfully treated with stem cell transplantation or keratoprosthesis surgery. In the case of stem cell transplantation, it is often desirable to have tube shunt surgery prior to surface rehabilitation surgery, such as a keratolimbal allograft, to minimize the potential deleterious effects of glaucoma drops on the transplanted tissue.

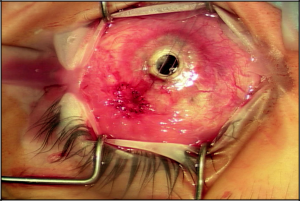

In our practice, when patients require 2 to 3 topical medicines preoperatively to control their glaucoma, we generally recommend glaucoma drainage implant surgery prior to undergoing keratolimbal allograft surgery. In general, the glaucoma worsens following the keratolimbal allograft surgery, and it is desirable to minimize topical glaucoma medicines following the stem cell transplant. It is also possible to place a tube shunt follow-ing keratolimbal allograft surgery. Careful attention needs to be taken to preserve the keratolimbal allograft integrity during the tube shunt insertion (Figure 3).

Tube insertion in a keratolimbal allograft patient starts by creating a conjunctival peritomy at the posterior lip of the keratolimbal allograft for approximately 100 degrees. The glaucoma drainage implant plate is placed in a routine fashion and secured to the sclera. A dissection is carried out between the sclera and keratolimbal allograft segment. Usually, this is fairly easy because there is already a plane between the keratolimbal allograft lenticule and the sclera. The segment of the keratolimbal allograft is then elevated, a 23-gauge needle is used to make an entry into the anterior chamber 1.5 mm posterior to the limbus, and the tube is inserted into the eye. After the tube is at the desired length and positioned in the anterior chamber, the keratolimbal allograft is then placed back in its original position and secured to the sclera with interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures. A small tissue patch graft is then placed behind the keratolimbal allograft segment, and the anterior portion of the tissue patch graft is positioned against and slightly posterior to the lip of the keratolimbal allograft to allow a small amount of “patch overlap.” This is done to ensure there is no gap in tube coverage by patch material (Figure 4). The conjunctival flap is closed by suturing the flap to the posterior lip of the keratolimbal allograft. I prefer a monofilament 9-0 Vicryl running suture on a Vas-100 needle.

Aniridia Fibrosis Syndrome

Aniridia fibrosis syndrome is described in aniridia patients that have undergone multiple surgeries in which there is progressive anterior cham-ber fibrosis. A retrolenticular and retrocorneal membrane forms, which can be seen clinically involving the ciliary body and anterior retina. Histopathologic evidence in this condition demonstrates extensive fibrotic tissue originated from the root of the rudimentary iris and entrapped in the intraocular lens (IOL) haptics.[12] Patients with aniridia and multiple prior surgeries (penetrating keratoplasty, tube shunts, cataract surgery) are at risk for aniridia fibrosis syndrome. Early recognition is important because early surgical intervention is recommended to prevent phthisis.[12] In our practice, pars plana vitrectomy with aggressive epiciliary membrane peeling has been successful in preventing some of these eyes from progressing to phthisis from ciliary fibrosis.

Key Points

- Aniridia patients present many unique challenges to the glaucoma surgeon.

- Tube shunt surgery, trabeculotomy, and goniotomy have shown the most favorable results.

- Early goniotomy should be considered in patients in whom angle changes are occurring that predispose them to developing aniridic glaucoma.

- Cyclodestructive procedures should be used with caution given the higher rates of severe complications in aniridia patients.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chen TC, Walton DS. Goniosurgery for prevention of aniridic glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(9):1144-1148.

- ↑ Filous A, Odehnal M, Brunova B. Results of treatment of glaucoma associated with aniridia [Czech]. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 1998;54(1):18-21.

- ↑ Adachi M, Dickens CJ, Hetherington J Jr, et al. Clinical experience of trabeculotomy for the surgical treatment of aniridic glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(12):2121-2125.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wiggens RE, Tomey, KF. The results of glaucoma surgery in aniridia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:503-505.

- ↑ Arroyave CP, Scott IU, Gedde SJ, Parrish RK II, Feuer WJ. Use of glaucoma drainage devices in the management of glaucoma associated with aniridia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):155-159.

- ↑ Lee H, Meyers K, Lanigan B, O’Keefe M. Complications and visual prognosis in children with aniridia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47(4):205-210.

- ↑ Wagle NS, Freedman SF, Buckley EG, Davis JS, Biglan AW. Long-term outcome of cyclocryotherapy for refractory pediatric glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(10): 1921-1926.

- ↑ Wallace DK, Plager DA, Snyder SK, Raiesdana A, Helveston EM, Ellis FD. Surgical results of secondary glaucomas in childhood. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(1):101-111.

- ↑ Okada K, Mishima HK, Masumaoto M, Tsukamto H, Takamatsu M. Results of filtering surgery in young patients with aniridia. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2000;49(3):135-138.

- ↑ Brandt JD, Casuso LA, Budenz DL. Markedly increased central corneal thickness: an unrecognized finding in congenital aniridia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(2):348-350.

- ↑ Whitson JT, Liang C, Godfrey DG, et al. Central corneal thickness in patients with congenital aniridia. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31(5):221-224.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 22. Tsai JH, Freeman JM, Chan CC, et al. A progressive anterior fibrosis syndrome in patients with post surgical congenital aniridia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1075-1079.