Trabeculectomy: Management of Postoperative Complications

| Primary authors |

|

|---|

By its nature, trabeculectomy typically entails much more risk than cataract surgery. However, thoughtful and successful management of post-operative complications can significantly reduce the risk of long-term harm to the patient.

Hypotony

Assessment

Complications of Hypotony

- Shallowed anterior chamber

- Mild to moderate shallowing

- Iris–cornea touch

- Lens–cornea touch

- Choroidal effusion/ciliary body detachment

- Choroidal hemorrhage

- Hypotony maculopathy

- Cystoid macular edema

Hypotony is one of the most dreaded complications of trabeculectomy and is one of the major causes of permanent reduction in visual acuity after glaucoma surgery. Hypotony itself, however, does not cause vision loss. Rather, the complications of hypotony, such as maculopathy, flat anterior chambers, and choroidal hemorrhages, can cause vision loss. The decision whether to intervene medically or surgically to reverse hypotony is dictated by the risk of vision loss. For example, a patient with an intraocular pres-sure (IOP) chronically in the range of 2 to 4 mm Hg can be safely observed if the anterior chamber is deep and the posterior segment examination is normal. Conversely, a flat anterior chamber with lens–cornea touch needs immediate intervention to prevent decompensation of the cornea. Hypotony maculopathy deserves definitive surgical treatment within several weeks to prevent permanent retinal damage (although significant recovery of vision can occur even after several years).[1]

Treatment for hypotony is directed at the underlying cause. In most cases, hypotony in the early postoperative period is due to overfiltration. Overfiltration is recognized by hypotony in the setting of a large and/ or diffuse bleb and relatively quiet eye. A bleb leak can also contribute to hypotony, and needs to be ruled out with a Seidel test. More rarely, hypotony may be caused by aqueous hyposecretion, either from marked postoperative inflammation, uveitis, or ocular ischemia. Hyposecretion associated with inflammation is best treated with cycloplegia and frequent topical, and pos-sibly systemic, steroids.

Medical Management

Stepwise Treatment of Overfiltration

- Medical and behavior management

- Taper topical steroids

- Cycloplegia

- Avoid eye rubbing and Valsalva, wear eye shield

- Minor procedures

- Viscoelastic injection

- Blood injection

- Major procedures

- Resuture the scleral flap ± excise avascular conjunctiva

- Graft material to seal flap, ± additional drainage surgery

Most cases of postoperative hypotony, however, are due to overfiltration and typically respond to a reduction of topical steroids. This will allow for additional scarring and a natural rise in IOP over days to weeks. A cycloplegic is often added, which can be especially helpful in anterior chamber shallowing. In some patients, it might be prudent to temporarily discontinue topical beta-blockers in the contralateral eye. I also encourage behavior changes to help reduce aqueous egress, including strict instructions against eye rubbing, wearing an eye shield at night, and avoidance of Valsalva maneuver.

If hypotony is more profound, with marked shallowing of the anterior chamber and/or ciliary body detachment, viscoelastic can be injected into the anterior chamber.[2][3] Injection may be done with a cannula through a previously created paracentesis or through clear cornea with a 25-to 30-gauge needle. Injection should be performed in a sterile manner with a lid speculum after prepping with povidone-iodine and instilling a topical antibiotic. The viscoelastic will increase IOP for 24 to 48 hours, which may allow additional bleb scarring or reattachment of the ciliary body and increased aqueous secretion. Healon (sodium hyaluronate) is a common initial choice, whereas Healon GV (sodium hyaluronate 1.4%) and Healon 5 (sodium hyaluronate 2.3%) will allow progressively more retention and ability to raise IOP. Often, viscoelastic injections need to be repeated several times until IOP is maintained spontaneously. If viscoelastic injection is done, the IOP should be checked 1 to 2 hours later to monitor for an IOP rise. Especially with Healon GV and Healon 5, IOP can rise very high and remain there for days, therefore, marked care must be used when using these high-viscosity agents after a trabeculectomy.

One option to induce bleb scarring is an autologous blood injection.[4] Although I personally have found this to be rarely successful, it may be worthwhile in a few cases. After prepping the arm and eye with povidone-iodine, approximately 0.5 cc of blood is drawn from an antecubital or other convenient vein with an 18- to 20-gauge needle. The needle is changed to a 25-gauge, inserted subconjunctivally temporal to the bleb, and advanced to inject 0.1 to 0.5 cc of blood into and behind the bleb. The blood must be injected promptly following removal from the vein to avoid clotting in the syringe. Hyphema is a common but self-limited complication.

Surgical Management

It is necessary to intervene surgically for hypotony that is threatening vision, however, this is uncommon.

Transconjunctival Scleral Flap Resuturing

The easiest technique is to directly resuture the scleral flap. If the bleb is not avascular and the scleral flap is visible, the flap may be resutured directly through intact conjunctiva using 10-0 nylon.[5] The eye should be prepped sterilely, and a cotton-tip applicator can be used to push down and flatten the bleb overlying the scleral flap. The edges of the flap are then identified and sutured tightly. Over several days to a couple of weeks, the sutures will migrate into the bleb and become buried. As the bleb elevates again and tissue migrates out of the sutures, the sutures will loosen and the eye pressure will decrease.

Direct Scleral Flap Resuturing

More commonly, the scleral flap is resutured after opening conjunctiva. The conjunctival flap may be fornix- or limbus-based; it is often convenient to re-open the original conjunctival incision as long as the conjunctiva has not become avascular. Avascular tissue may not heal well and is prone to persistent leaks if incised. If avascular conjunctiva is believed to be playing a role in hypotony, it should be excised along with a narrow margin of healthy conjunctiva to ensure there is a bleeding, healthy, viable edge. The scleral flap is then identified, and if partially scarred down, may be sharply re -elevated and freshened. The flap should then be sutured tightly using 10-0 nylon to achieve a watertight (or nearly watertight) closure. The conjunctiva should then be closed in a watertight fashion, and suture lysis of the scleral flap sutures performed as needed. Achieving a controlled elevation of IOP in the early postoperative period may reverse some of the signs and symptoms of hypotony maculopathy and speed resolution of choroidal effusions.

Scleral Flap and Bleb Revision

Not infrequently, the scleral flap is found to be friable, partially “melted,” or otherwise damaged from antimetabolite exposure and surgical manipulation, and it may be impossible to adequately restrict flow by resuturing the flap. These situations can be addressed by suturing graft material, typically sclera or pericardium, over the entire scleral flap site using 10-0 nylon. Although the graft should be sutured down tightly and securely, the closure may not need to be watertight because the new graft will typically scar down and permanently seal the old trabeculectomy site. Although some have tried to suture the new graft material in such a way to allow continued partial flow of aqueous posteriorly into the bleb, I have not found this technique to be successful.

As expected, covering the old trabeculectomy site frequently results in uncontrolled pressure. When sacrificing a bleb with graft material, I will frequently place a glaucoma tube shunt (typically a Baerveldt 350 mm2 concomitantly to provide continuing control of IOP).

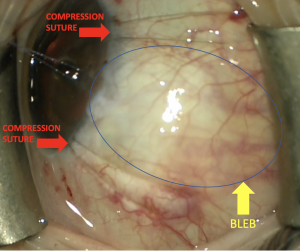

Techniques for limiting the diffuse bleb (Figure 1): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U10-cGF14RU

Choroidal Effusions

Although choroidal effusions are often approached as a distinct complication that requires directed treatment, I think it is better to consider them to be a complication of hypotony. I have found that drainage of choroidal effusions is rarely indicated. Rather, treatment of the underlying hypotony is typically curative.

Choroidal effusions themselves rarely cause permanent vision loss, although they are a risk factor for choroidal hemorrhage. Many effusions, even relatively large ones, can be carefully observed, while waiting for medical management, to allow spontaneous hypotony resolution. If effusions are “kissing,” if there is lens–cornea touch, or if chronic ciliary body detachment is contributing to hypotony, drainage may be indicated as part of trabeculectomy revision.

Aqueous Misdirection

Assessment

Glaucoma surgery is one of the most common reasons that eyes develop aqueous misdirection. Aqueous misdirection was previously called “malignant glaucoma,” a moniker it earned due to the extremely high rate of blindness that occurred before ophthalmologists learned to treat this condition. Today, prompt recognition and appropriate treatment of this condition should prevent serious vision loss in most circumstances.

Aqueous misdirection is classically recognized by a shallow to flat anterior chamber and marked elevation of IOP. However, functioning outflow surgery can significantly blunt or prevent the elevation in IOP secondary to aqueous misdirection. For example, a markedly shallowed anterior chamber and an IOP of 16 mm Hg is highly suggestive of aqueous misdirection in the setting of recent trabeculectomy or tube shunt (by contrast, a shallowed chamber of overfiltration would typically be associated with IOP in the low single digits). Because pupillary block and choroidal hemorrhage can also present with a shallowed chamber and elevated IOP, a patent iridotomy and complete fundus exam are important before making the diagnosis of aqueous misdirection.

Medical Management

Initial treatment for aqueous misdirection is intense cycloplegia, augmented by topical aqueous suppressants and acetazolamide. Systemic hyperosmotics (intravenous mannitol, 0.5 to 1.5 gm/kg or oral glycerine 1 to 1.5 gm/kg) can be effective but must be used cautiously due to their systemic side effects. Often, medical management alone is not sufficient.

Laser Management

(a) anterior chamber via a clear cornea incision or

(b) through the pars plana. Alternatively, the YAG laser can be applied through a peripheral iridectomy to disrupt the zonules as well as the anterior vitreous face. Again, however, this is typically helpful only in pseudophakes.

In pseudophakes, aqueous misdirection will often respond to nd:YAG capsulotomy and anterior hyaloidotomy to disrupt the anterior hyaloid face. After performing a typical nd:YAG capsulotomy, additional laser shots can be applied into the anterior vitreous. If successful, the anterior chamber will begin to deepen rather quickly, typically while the laser is still being performed. Retinal tears are a small risk when lasering the vitreous body.

Surgical Management

Complete removal of the vitreous body by a pars plana vitrectomy is currently the gold standard for curing aqueous misdirection. The vitreoretinal surgeon must be sure to break the anterior hyaloid face, which can be difficult to do in phakic patients without damaging the lens capsule.

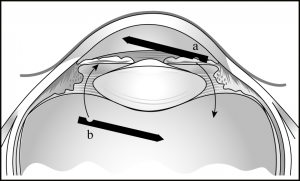

Rarely, aqueous misdirection can persist despite a complete pars plana vitrectomy, presumably due in part to the presence of the retained vitreous skirt. In these cases, an iridozonulohyaloidectomy (IZH; this term was coined by Ike Ahmed, MD) should be performed (Figure 5-1). This can be done by passing an automated vitrector from the posterior segment, up through the zonules and iris, into the anterior chamber (or similarly from the anterior chamber down through iris and zonules into the anterior vitreous). A combined pars plana vitrectomy and IZH are highly curative but can be performed only in pseduophakes or aphakes. In phakic patients, the lens may need to be removed to allow resolution of aqueous misdirection.[6]

Some anterior segment surgeons have found that performing a limited anterior vitrectomy and IZH has allowed them to successfully treat aqueous misdirection without involving a vitreoretinal surgeon. I typically do not do this myself, but rarely I utilize this maneuver for “intraoperative aqueous/ infusion misdirection.”

Bleb Leak

Assessment

Although a bleb leak may lead to hypotony, the most serious complications are blebitis and endophthalmitis. It is for this reason that a frank bleb leak must always be treated.

A Seidel fluorescein test for leakage should be performed whenever a patient with a filtering bleb presents with epiphora, hypotony, or a low/flat bleb and hypotony. Additionally, it may be prudent to periodically check for leaks in high, thin avascular blebs.

Upon discovery of a leak, blebitis should be ruled out by ensuring there is no conjunctival injection, bleb infiltrate, or anterior chamber inflammatory cells. Initially, a simple bleb leak can be managed conservatively. The patient should be instructed to avoid touching the eye and practice good hygiene to avoid infection.

Medical Management

A majority of bleb leaks will resolve with conservative management, especially those leaks that occur in the early postoperative period. Shortly after a trabeculectomy, leaks will often respond to simply tapering topical steroids to allow scarring and healing.

Typically, when the leak is discovered, a topical antibiotic, such as a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone, is started to prevent the progression to blebitis. Although it is likely prudent to do so, it is not totally clear whether prophylactic antibiotics truly prevent blebitis or simply promote the emergence of a resistant organism.

Optimization of the ocular surface can help support healing of the leak. Erythromycin ointment or azithromycin gel, through their anti-inflammatory action and improvement in meibomian gland function, may help promote a healthy ocular surface and potential reepithelialization of the leak. Systemic doxycycline, up to 100 mg twice daily, can also improve ocular surface health in the same way. Additionally, its inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases may further promote closure of the leak.

The leak is likely kept open by continual aqueous flow through the conjunctival defect. Therefore, measures should be taken to reduce fluid egress through the leak. The patient should be instructed to avoid Valsalva, bending, and eye rubbing. Wearing an eye shield during sleep can be very helpful. To further reduce flow through the leak, aqueous suppressants can be tried.

Pressure-patching the eye for 24 hours may allow closure of the leak by temporally tamponading flow. Similarly, a bandage contact lens may be placed to completely cover the leak. Because infection and corneal decompensation are the main risks of a bandage contact lens, a topical third- or fourth- generation fluoroquinolone needs to be added, and the patient should be examined at least weekly. Typically, I replace the bandage lens every 1 to 2 weeks and will allow 2 to 4 weeks for healing before abandoning the bandage lens.

Surgical Management

If the leak occurs in a localized bleb (one surrounded by a ring of scar tissue), needling may be tried to allow aqueous to diffuse more broadly and lower the pressure within the bleb. In some cases, this may promote closure of the leak and prevent a return to the operating room.

The simplest repair is suturing the leak. Suturing is most likely to be helpful in the early postoperative period when the conjunctiva is actively healing and when the leak occurs in the previous conjunctival incision line. However, because every needle pass can create more leaks, resuturing is not helpful for thinned or avascular tissue.

If the leak does occur with thinned conjunctiva, most likely the leak will have to be repaired by conjunctival advancement, which provides an acceptable level of safety and success.[7] First, a peritomy is performed around the base of the bleb, taking care to keep the incision within bleeding, viable conjunctiva. Extensive undermining should then be performed to ensure fresh conjunctiva can be advanced to the limbus without tension. The avascular bleb tissue can then be deepithelialized with light cautery and the healthy conjunctiva advanced over the old bleb to the limbus. The closure should be as close to watertight as possible.

A few modifications to this technique may be helpful. The avascular, leaking bleb can be completely excised. Additional scleral flap sutures may be placed to reduce flow and promote healing of the newly advanced conjunctiva without leak; suture lysis may be performed a later date as necessary. If the conjunctiva cannot be closed without excessive tension, then a conjunctival autograft can be used or the bleb can be sacrificed by sealing it with donor graft material and placing a glaucoma tube shunt.

Blebitis

Assessment

Blebitis can rapidly progress to endophthalmitis and profound vision loss. Therefore, blebitis requires early recognition and aggressive management. The initial symptoms of blebitis are pain or discomfort, redness of the eye, and decreased vision. There may be antecedent epiphora from a bleb leak. Signs on examination are injection of the bleb and/or surrounding conjunctiva, as well as a bleb infiltrate, giving the bleb a white or milky appearance. Occasionally, a hypopyon within the bleb can be seen. An anterior chamber reaction is common. If there are any vitreous inflammatory cells, retinal consultation should be obtained immediately to rule out endophthalmitis.

Management

If there is any question of blebitis, the patient should be started on a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone and rechecked in 24 hours or less. Alternatively, fortified antibiotics, typically vancomycin 25 to 50 mg/mL plus ceftazidime 50 mg/mL or tobramycin 14 mg/mL can be used for more assured microbial coverage (I tend to avoid the aminoglycosides, such as tobramycin, if there is any risk of intraocular penetration through a bleb leak due to their potential for extreme retinal toxicity). Typical dosing should begin with 1 drop every 15 minutes for the first hour, then 1 drop hourly thereafter. Subconjunctival injections of the same fortified anti-biotics may be added if the patient’s ability to fully adhere to the medical regimen is in doubt. Frequent follow-up is required to ensure the blebitis is resolving and not progressing to endophthalmitis.

If endophthalmitis is diagnosed, prompt treatment is essential. A pars plana vitrectomy is indicated earlier for a bleb-associated endophthalmitis than for a postcataract surgery endophthalmitis, although intravitreal anti-biotic injections remain a viable alternative.

Choroidal Hemorrhage

Assessment

Choroidal hemorrhages occur most commonly in the setting of hypotony. Other risk factors are glaucoma, systemic hypertension, vascular disease, and eyes that have had prior vitrectomies.[8][9] Systemic anticoagulation may not increase the risk of choroidal hemorrhage, but can make a small hemorrhage become one that is devastating.

Choroidal hemorrhages are recognized by pain and a dark choroidal mound on fundus examination. B-mode ultrasonography is confirmatory. Additional examination findings depend on the size of the hemorrhage and include shallowing or flattening of the anterior chamber, increased IOP, and variable loss of vision.

Management

Small, self-limited choroidal hemorrhages require observation only, along with instructing the patient to avoid Valsalva, eye rubbing, and,

if possible, systemic anticoagulation. Larger hemorrhages may benefit from cycloplegia and topical or systemic steroids. If the anterior chamber is severely shallowed, if the choroidal hemorrhages are “kissing,” or if IOP is uncontrolled, drainage is indicated. I typically refer patients to my vitreoretinal colleagues for drainage of choroidal hemorrhage, although some anterior segment surgeons prefer to perform the surgery themselves.

Key Points

- Hypotony can often be observed but needs to be treated when it is causing (or likely will cause) vision-threatening complications.

- Most early postoperative hypotony will resolve spontaneously if given enough time; supportive measures can help buy time for early bleb scarring to bring up the IOP.

- All bleb leaks need to be addressed, and conjunctival advancement is often the best choice for late-onset leaks when more conservative measures fail.

- Successful management of aqueous misdirection may respond to nd:YAG laser disruption of the anterior vitreous face but often requires a pars plana vitrectomy and/or an iridozonulohyaloidectomy.

References

- ↑ Oyakhire JO, Moroi SE. Clinical and anatomical reversal of long-term hypotony maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(5):953-955.

- ↑ Salvo EC Jr, Luntz MH, Medow NB. Use of viscoelastics post-trabeculectomy: a survey of members of the American Glaucoma Society. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999;30(4):271-275.

- ↑ Hoffman RS, Fine IH, Packer M. Healon5 as a treatment option for recurrent flat ante-rior chamber after trabeculectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(4):635.

- ↑ Okada K, Tsukamoto H, Msumoto M, et al. Autologous blood injection for marked overfiltration early after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79(3):305-308.

- ↑ Maruyama K, Shirato S. Efficacy and safety of transconjunctival scleral flap resuturing for hypotony after glaucoma filtering surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246(12):175-176.

- ↑ Tsai JC, Barton KA, Miller MH, Khaw PT, Hitchings RA. Surgical results in malignant glaucoma refractory to medical or laser therapy. Eye (Lond). 1997;11(Pt 5):677-681.

- ↑ Burnsteil AL, WuDunn D, Knotts SL, Catoira Y, Cantor LB. Conjunctival advancement versus nonincisional treatment for late-onset glaucoma filtering bleb leaks. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(1):71-75.

- ↑ Obushowska I, Mariak Z. Risk factors of massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage during extracapsular cataract extraction surgery. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(6):712-717.

- ↑ Moshfeghi DM, Kim BY, Kaiser PK, Sears JE, Smith SD. Appositional suprachoroidal hemorrhage: a case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(6):959 963.